2008 Financial Crisis Explained: How Michael Burry Predicted the Crash and Made Billions

Learn how Michael Burry foresaw the 2008 financial crisis and turned his prediction into massive profits through bold investment moves.

This is one of the Key Instruments That Made Michael Burry Billions

Today we’re going to analyze one of the key financial instruments that allowed Michael Burry, with his fund Scion Asset Management, to earn hundreds of millions of dollars during the Great Recession of 2008.

Before diving into a detailed analysis, we should go over a brief summary to set the scene.

I promise it won’t be too dense 😉

The Beginning

It all started with the economic situation in the United States after the dot-com crisis and the 9/11 attacks in New York. These events drastically worsened market conditions.

The NASDAQ lost 72% of its value by 2002, and the S&P 500 dropped 14% on the day of the Twin Towers attack. Many companies went bankrupt and had to lay off workers, pushing unemployment to 6%. This, in turn, led people to cut expenses, withdraw money from banks, and thus the recession chain was set in motion.

The only way to restore consumption and re-stimulate the economy was through expansionary policies by the Federal Reserve. This way, credit became cheaper, and companies had more liquidity to restore, expand, and hire workers—helping to revive consumer spending.

These policies brought interest rates down to as low as 1% by 2003, setting the stage for a new economic cycle and the perfect conditions for another bubble.

The Housing Market

Given the situation we just described, credit became extremely accessible. If you borrowed $100, you had to return $100 + $1. That promoted a scenario where everyone began taking out loans for things like student debt, personal loans, business funding, and especially home purchases—mortgages.

The mindset was simple:

James, 25 years old, wanted to live with his girlfriend in a house overlooking a golf course with a nice garden and a dog. They wanted to live the American Dream 2.0—replicating what their grandparents did in the roaring 1920s.

James and his wife saw two things:

a) Mortgage loans were very cheap.

b) Houses always go up in value, so there was "no risk."

And here lies the mistake. James didn’t want a modest apartment that matched his income…

They wanted a $500,000 house, but they had just finished their studies. James worked at McDonald's and his wife was a clothing store assistant.

They went to a bank and asked for a 30-year mortgage of $300,000. The bank didn’t think twice and said: Sure! They didn’t ask about their financial situation or anything at all.

The bank knew there was enough demand for the house, and if the couple couldn’t pay the mortgage, someone else would buy it—because the real estate sector was “strong.”

So now we have a young couple in a house far beyond their means, with a loan that would drill them for at least 10 years, and a home next to an artificial golf course 30 km from downtown Nashville. A house that might have actually been worth $150,000 was sold to them at over 3.3 times its real value.

And there were thousands—millions—of similar couples, tragically lured into a fantasy, partly caused by poor risk control and lack of diversification in the banking system.

Everything's Fine… Until It Isn’t

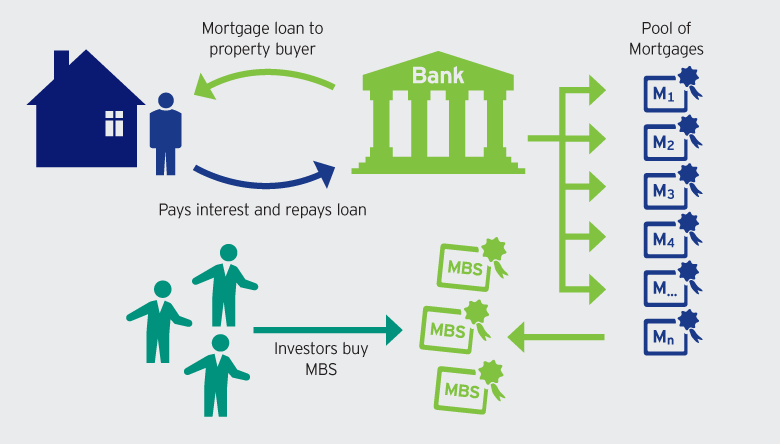

As shown in the example above, banks held thousands of mortgages they couldn’t afford to keep until maturity—they needed immediate liquidity to continue the lending cycle.

So they sold these mortgages to financial institutions, which created special products that could be bought by investors.

In short:

The mortgage went from the bank to a financial institution, and this institution sold a special package to investors so they could participate in the real estate market and benefit from the mortgage payments—without owning the home or the loan directly.

These investors bought special packages called MBS (Mortgage-Backed Securities) and made money as long as the borrowers made their monthly payments.

But here’s the problem:

But here’s the problem:

If borrowers stopped paying, the MBS would default. Investors would sell off the MBS quickly, since they lost value.

The credit chain weakened because the underlying asset—the houses—started to lose value.

Home prices had gone up without solid fundamentals, often for homes in distant, undesirable areas.

At some point, buyers stopped purchasing homes because they were too expensive. Meanwhile, wages didn’t increase, and jobs were still mostly unskilled.

As a result, the guarantees behind the loans became insufficient, and risks weren’t properly covered.

The Clever Michael Burry

As we mentioned, these MBS products were made of subprime mortgages. That means banks had lent money to people who couldn’t afford to repay their debts. When those people defaulted, banks were left holding toxic assets—because the collateral (the houses) had also lost value.

But Michael Burry and his team analyzed the assets behind those MBS before the crash. They realized they were mostly subprime mortgages.

So, they approached several banks to negotiate insurance against defaults on those mortgages—essentially placing a bet that people would not be able to pay them.

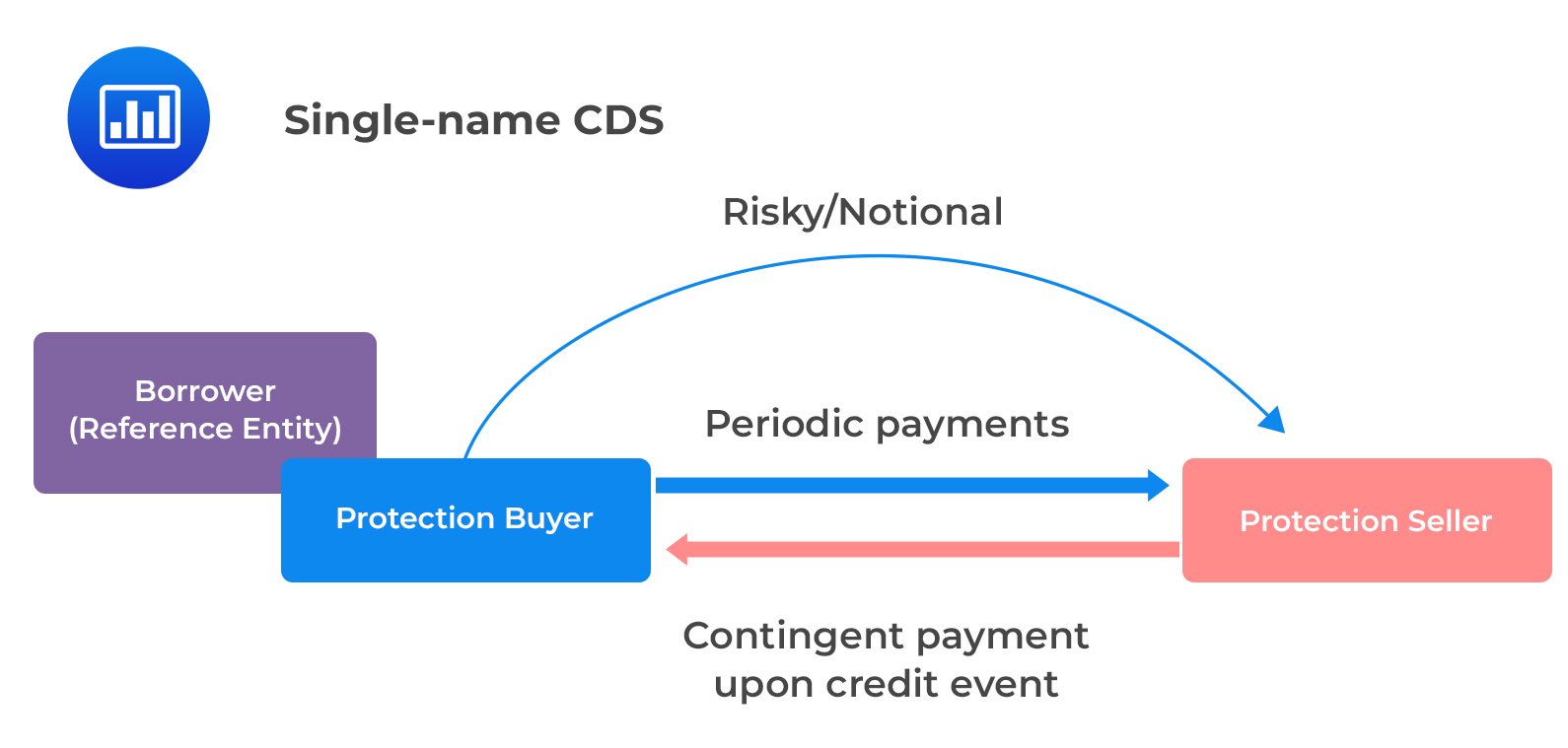

They negotiated what’s called a CDS (Credit Default Swap)—a contract where two parties agree to exchange capital flows if a specific event occurs.

If a mortgage default occurred, the bank that sold the CDS would have to pay the agreed amount to Michael Burry’s fund. But while the event didn’t happen, the CDS buyer (Burry) had to regularly pay premiums to the counterparty.

In the End

Thanks to this strategy, Michael Burry earned over $800 million for his fund in just a few months.

If you liked this quick analysis and explanation, we’d love for you to share the article and check out what we’re building to help democratize finance!

Thank you for reading.

Interested in this topic?

Discover how Siprifi is revolutionizing decentralized finance with innovative blockchain risk management solutions.

Visit Siprifi